Critiquing World Music

"One good thing about music....

When it hits, you feel no pain."

-Bob Marley

This week, National Geographic launched a world music website

When I saw the site, I scrolled through samples of paranda, afrobeat and soukous, gleeful that I could transform myself into a global D.J. of African Diaspora rhythms, using nothing more than my laptop. But when I finished scrolling I realized that there was something ever so slightly disturbing about the site.

The term "world music" has been overused over the past decade, and I think it is ripe for being critiqued. Friends and colleagues in my circle say the term "world music" is a misnomer: it's a Western shorthand for too many genres and it's offensive in its vagueness. A literature professor friend of mine (also the best music writer and memoirist on this side of Flatbush Ave) boycotts events that reference "world music."

National Geographic explains its use of the term with a glossiness that surprised me as a reader of old magazines featuring crunchy stories on arctic wildlife, or Ice Tombs in Siberia, or excavated tombsites in Egypt.

"World music is Israeli reggae and Japanese klezmer. It's rock and roll from the Sahara and flamenco with a hip-hop breakbeat; it's digital bossa nova and Irish sean nos with an African pulse. It's downhome country music from someone else's country and smooth, urban R&B from the mega-cities of the Southern Hemisphere. It's cowboy music from Venezuela and Persian classical music from L.A. It's music that transcends borders...it's the soundtrack of globalization, and the sound of the world we live in today."

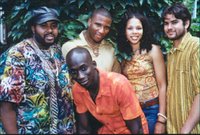

Derrick Ashong, leader of Soulfege,

an afrobeat/hip life/hop band out of Ghana, Boston, D.C. and Philadelphia, is not a fan of the term, which he considers meaningless. "By that definition everything is world music," he says.

"When people say 'world,' they put anything in there." says Derrick. "If your music is not from the US or not from Europe, it's world music. So when they say world music, it could be Turkish dervish dancing, right? It could be a traditional tubla playing or it could be mbalax, you know what I'm saying? Or it could be reggae. I mean what is world music?"

A slippery road for a brother whose band received the Boston Music Award's 2005 nomination for "Best World Music..."

As Derrick explains it, his band's unique sound pays tribute to some of the common roots of African and African-American music: the funk that laid the beats for early hip hop, the spoken word chat that was early dance hall and laid the foundation for New York rap, the West African percussive styles that laid the foundation for reggae and other forms of Afro-Caribbean music. "We take elements of hip-hop, highlife, and reggae, we fuse them with gosepel/R&B, doo-wop influenced vocals and we have a very very groovy band at the core with gorgeous...vocals on top" says Derrick. "We go to the youth music, so our music is not Hip Life, but we're doing the same thing that the hip-life guys are doing - we're just taking in more Caribbean and American influences."

So in the end, I ask, is there no usefulness to categorizing, labeling, and separating out "our" music? Surely the all-embracing quality of "world music" - and the diversity of its fan base - challenge the notion that there is only a market for the superficial, commercialized categories of a conglomorated pop-rock Western music industry. "World music" makes room for small developing country music, sacred and traditional music, and other forms of cultural expression that have been excluded from the maintsream for years. Theoretically, it places this music before an open-minded and international audience.

So for those of us interested in maintaining the communities and music fan forums that artificial categories can unknowingly create, I think a question remains. We can reject the oppressive economics that have kept our favorite artists hidden on the back shelves of Tower Records. But how do we find new ways to describe innovative music that reflects the common roots that are shared across every Diaspora? Music like Soulfege's?

For the time being, here are some "world music" sites that I recommend.

http://www.nationalgeographic.com

http://www.calabashmusic.com

http://www.afropop.org

http://www.rootsworld.com/rw

NL

When it hits, you feel no pain."

-Bob Marley

This week, National Geographic launched a world music website

When I saw the site, I scrolled through samples of paranda, afrobeat and soukous, gleeful that I could transform myself into a global D.J. of African Diaspora rhythms, using nothing more than my laptop. But when I finished scrolling I realized that there was something ever so slightly disturbing about the site.

The term "world music" has been overused over the past decade, and I think it is ripe for being critiqued. Friends and colleagues in my circle say the term "world music" is a misnomer: it's a Western shorthand for too many genres and it's offensive in its vagueness. A literature professor friend of mine (also the best music writer and memoirist on this side of Flatbush Ave) boycotts events that reference "world music."

National Geographic explains its use of the term with a glossiness that surprised me as a reader of old magazines featuring crunchy stories on arctic wildlife, or Ice Tombs in Siberia, or excavated tombsites in Egypt.

"World music is Israeli reggae and Japanese klezmer. It's rock and roll from the Sahara and flamenco with a hip-hop breakbeat; it's digital bossa nova and Irish sean nos with an African pulse. It's downhome country music from someone else's country and smooth, urban R&B from the mega-cities of the Southern Hemisphere. It's cowboy music from Venezuela and Persian classical music from L.A. It's music that transcends borders...it's the soundtrack of globalization, and the sound of the world we live in today."

Derrick Ashong, leader of Soulfege,

an afrobeat/hip life/hop band out of Ghana, Boston, D.C. and Philadelphia, is not a fan of the term, which he considers meaningless. "By that definition everything is world music," he says.

"When people say 'world,' they put anything in there." says Derrick. "If your music is not from the US or not from Europe, it's world music. So when they say world music, it could be Turkish dervish dancing, right? It could be a traditional tubla playing or it could be mbalax, you know what I'm saying? Or it could be reggae. I mean what is world music?"

A slippery road for a brother whose band received the Boston Music Award's 2005 nomination for "Best World Music..."

As Derrick explains it, his band's unique sound pays tribute to some of the common roots of African and African-American music: the funk that laid the beats for early hip hop, the spoken word chat that was early dance hall and laid the foundation for New York rap, the West African percussive styles that laid the foundation for reggae and other forms of Afro-Caribbean music. "We take elements of hip-hop, highlife, and reggae, we fuse them with gosepel/R&B, doo-wop influenced vocals and we have a very very groovy band at the core with gorgeous...vocals on top" says Derrick. "We go to the youth music, so our music is not Hip Life, but we're doing the same thing that the hip-life guys are doing - we're just taking in more Caribbean and American influences."

So in the end, I ask, is there no usefulness to categorizing, labeling, and separating out "our" music? Surely the all-embracing quality of "world music" - and the diversity of its fan base - challenge the notion that there is only a market for the superficial, commercialized categories of a conglomorated pop-rock Western music industry. "World music" makes room for small developing country music, sacred and traditional music, and other forms of cultural expression that have been excluded from the maintsream for years. Theoretically, it places this music before an open-minded and international audience.

So for those of us interested in maintaining the communities and music fan forums that artificial categories can unknowingly create, I think a question remains. We can reject the oppressive economics that have kept our favorite artists hidden on the back shelves of Tower Records. But how do we find new ways to describe innovative music that reflects the common roots that are shared across every Diaspora? Music like Soulfege's?

For the time being, here are some "world music" sites that I recommend.

http://www.nationalgeographic.com

http://www.calabashmusic.com

http://www.afropop.org

http://www.rootsworld.com/rw

NL